In Pressure, a new story from the Content Standard, we investigate the mounting pressure marketers are under to change how they connect with audiences. Learn how an evolution in the way we create, discover, and share information has fundamentally shifted the way enterprise marketing teams operate.

Somehow, the nation had climbed out of what felt like the pits of hell. The 1950s in the United States saw dramatic economic growth, widespread adoption of television and advertising; of moving to the suburbs and owning multiple cars; of buying for excess and dumping what felt old fashioned. Coming out of World War II, the 1950s felt both socially conservative and deviant, politically secure and borderline spiraling out of control.

We wanted—and felt that we deserved—more. More high-end clothing; replaceable kitchen appliances; bigger homes in the suburbs, with white-picketed fences and grass for the children to play, and a dog or cat, named Toby or Spot. We craved status and reputation; country clubs and community organizations; a TV set to watch together as a family; funny shows with celebrities; ads to keep our tastes ever-evolving.

All across the country, people wondered if this was the better life that they had fought to achieve, or if this new perception of comfort was just a figment of their war-torn imagination.

The United States was never more optimistic and prosperous in the 1950s, but today there is an underlying feeling of pressure that lingers. Television marked the advent of interrupt advertising, which has only diversified and grown since the beginning of the post-war economic boom.

As new technology has come and gone, the goal of marketing has remained largely unchanged. Whether developing an advertising campaign for the web or creating a new commercial for broadcast TV, brands are quick to use any channel available to put their product and message in front of the biggest audience possible. This constant battle for consumer attention has put enormous amounts of pressure on both marketers and the people they’re trying to reach. Now, being “always on” isn’t an option—it’s part of everyday life.

In Pressure, a new story from the Content Standard, we investigate the mounting stress marketers are under to adapt to evolving consumer preferences and change how they connect with their audiences.

We’ll follow the stories of Karen Guglielmo, Content Marketing Manager at Iron Mountain, Bridget Burns, Social Media Strategist at Tom’s of Maine, Sree Lenhart, Senior Content Strategist at Skyword, and Thomas Pening, Global Content Strategy at Skyword, as they talk about the pressures they face every day in marketing and how they’ve overcome (or begun to overcome) these barriers.

But let’s start at the beginning.

The United States was a growing force to be reckoned with in the 1950s (we had Duopeds before hover boards were chic!). The population had surpassed 150 million, an increase of 10.4 percent since 1940. Wages were double or triple what they had been in 1935.

The popularity of television in the United States also skyrocketed in the 1950s. Seventy-seven percent of households purchased their first TV set during the decade. By 1951, regular live network service reached the West Coast via microwave transmitters, establishing coast-to-coast national coverage for the first time.

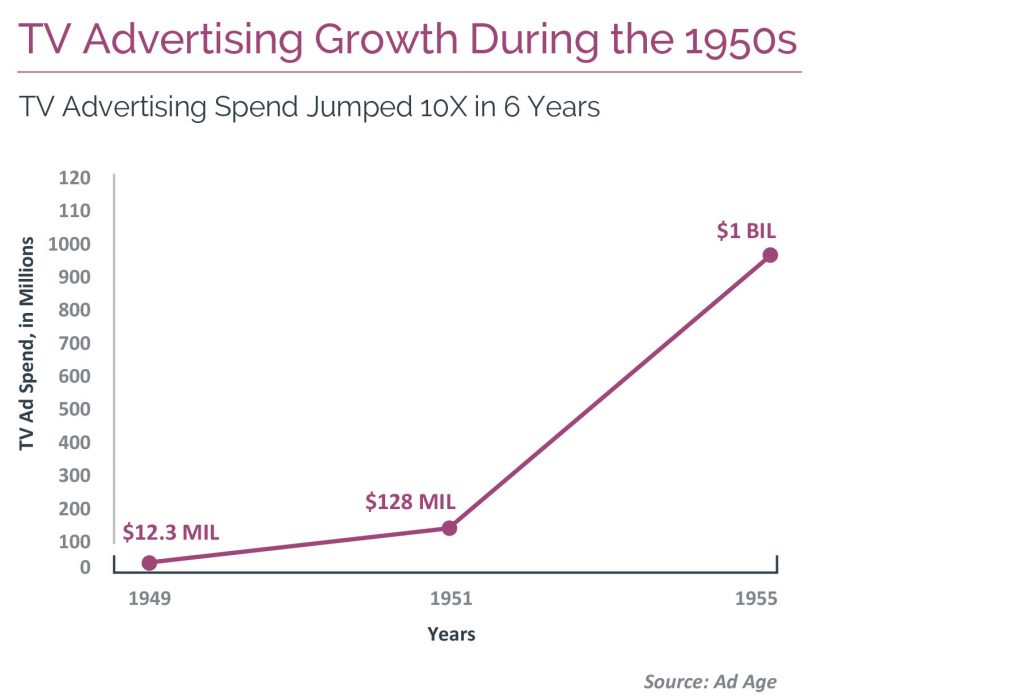

TV quickly became the leading advertising medium in the United States with ad spend growing from $12.3 million in 1949 to $128 million in 1951. Advertisers spent $1 billion on TV by 1955, and by 1957 Americans were watching 450 stations across the country on 37 million TV sets.

In the first half of the decade, US advertising was still ramping up to meet the demand of new products. However, demand quickly turned into a social anxiety to always have the “new and improved” version of everything. For the first time, advertisers focused their strategies on selling techniques that relied upon methods such as motivational research, demographic targeting, and generational marketing. These techniques proved successful as Americans looked to brands for guidance on how to live a better life.

Overall, the annual advertising industry billings grew from $5.7 billion in 1950 to $12 billion in 1960. Traditional media, like radio and print, suffered at the latter half of the decade, as TV became the cornerstone of many national media plans. Sitting around the television set as a family became a nightly tradition, giving advertisers uncompromised access to a growing audience.

Advertising during this period portrayed the ideal modern family—a mother, father, son, and daughter. Children became targets of advertising, and advertisers forayed into the production of original programming to reach the widest possible audience. Today, it’s hard to imagine a brand like Google creating and sponsoring an entire TV series on ABC, but in the 1950s families gathered around television sets to watch shows like The Colgate Comedy Hour, Hallmark Hall of Fame, and Texaco Star Theatre.

Brands, testing out new advertising methods, also conceptualized and created public personas—the Man in the Hathaway Suit and the Marlboro Man—to connect with audiences through relevance, authenticity, and aspiration.

TV and advertising existed hand-in-hand, as technology evolved and brands fine-tuned the most effective way of slinging their products to the masses through the country’s most prominent communication channel. Advertisers were quick to realize that by rooting their spots in current events they’d connect with their audiences at emotional levels. This led to full primetime blocks in which programs kept Americans aware of socioeconomic changes, broken up by ads that promised a better quality of life if you bought their product.

Recently, TV’s influence has diminished in both the hands of the marketer and the eyes of the consumer.

The idealized modern family no longer applies. Consumerism isn’t anything new. There will always be the latest and greatest product—it’s not a unique value proposition. Furthermore, subscription television is no longer the place people go to escape their everyday lives—it’s an inflexible medium that’s more interruptive than entertaining.

So, along with these new sentiments toward purchasing things, people are turning away from television at a rate faster than its growth in the 1950s, instead choosing ad-free services like Netflix and Hulu. For advertisers, the world that once felt balanced and fair has suddenly fallen apart.

To regain balance, advertisers now realize they have to create experiences that don’t add stress to people’s lives, but relieve it. This reality has led to new ways in which we discover, read, and share stories.

Television saw marked growth decades after its mass adoption in the 1950s, even as the internet blossomed into the most dominant communication and entertainment channel today.

In the last decade, the tides have begun to shift course, causing many industry analysts to question the longevity of the age-old TV model. In January 2013, Morgan Stanley analyst Benjamin Swinburne and team published a report that showed broadcast TV’s audience had collapsed by 50 percent since 2002.

Instead of focusing on this decline, pay TV providers (Comcast, Verizon, etc.) jacked up advertising prices, offering brands access to still a largely unfragmented audience. They also increased subscription costs for their customers. While audience attention has tapered off, the industry as a whole is still financially healthy.

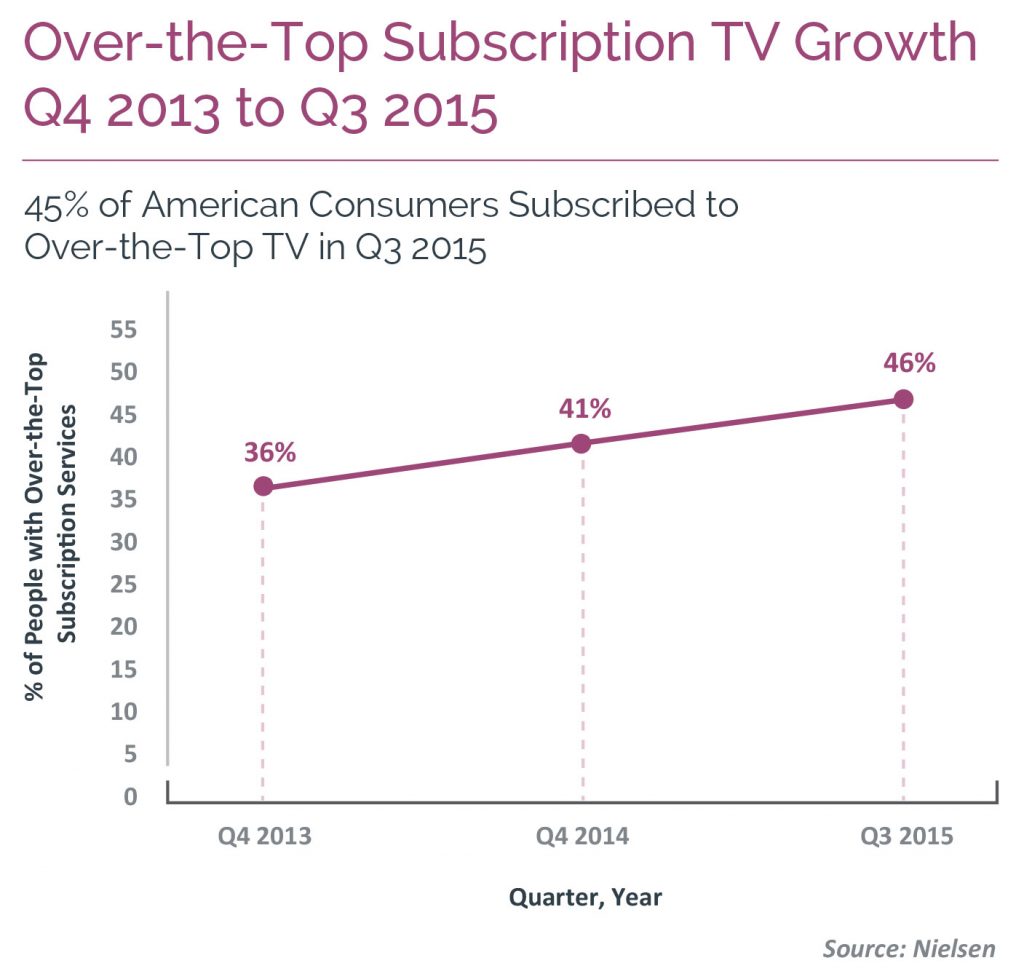

TV companies have seen the early signs of transformation taking place in how people discover, consume, and share information. And throughout the years, report after report, these organizations have failed to enact change to course-correct their collapsing business models. They turned a blind eye to what their audiences were craving. This, in turn, opened the door for the rise of streaming services like Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Instant Video, etc, and consumer demand for these platforms skyrocketed.

In 2014, Nielsen revealed Q4 numbers in its Total Audience Report that showed adults watched 13 fewer minutes of pay TV year-over-year. That dip was in addition to six fewer minutes between 2012 and 2013.

Less than six months after the Nielsen report, a new survey from Deloitte found that US consumers were more inclined to stream entertainment from an internet service than tune into live TV. According to the organization, 42 percent of Americans indicated that video-streaming services had overtaken live programming as the viewing method of choice. For those consumers ages 14 to 25, nearly 72 percent cited streaming entertainment as their most valuable service, compared to 58 percent who said the same about TV.

Nearly 72 percent of 14 to 25 year-old consumer cited streaming entertainment as their most valuable service.”

Another way TV executives sought to solve this problem directly was by launching new original content across channels. They thought that, by sheer nature of television, this would increase advertising opportunities for brands. New programs geared toward niche markets would give advertisers better promotional avenues. But original programming wasn’t the issue—November 2015 research from RBC Capital Markets found that for more than half of US Internet users, access to original content did not influence their decision to subscribe to Netflix.

What did? Lack of ads. And TV wasn’t the only industry feeling the pressure of transformation.

Similar to television advertising, banner ads were born out of necessity on a medium that grew much faster than many had expected. With television, the cost to broadcast began to grow fast and furiously, requiring TV companies to work with brands who could offset some of those production costs.

When it came to building online presences, media companies invented banner advertisements as a way to finance these new digital destinations. The New York Times reports that HotWired, a digital publication by Wired magazine, published the first banner ads on October 27, 1994, with partners AT&T, Volvo, and Zima.

These ads were born out of necessity—not because there was any supporting research that suggested they would be a good idea. But like most transformative best practices, once HotWired began using banner ads, their competitors and the industry as a whole jumped on board.

In his article titled “Fall of the Banner Ad: The Monster That Swallowed the Web,” The Times tech reporter, Farhad Manjoo, writes:

“[Banner ads] have ruined the appearance and usability of the web, covering every available pixel of every page with clunky bits of sponsorship. More than that, banner ads have perverted the content itself.”

He continues:

“Because they are so ineffective, banner ads are sold at low prices for high volume, which means to make any money from them, sites need to pull in major traffic. This business model instilled the idea that page views were a paramount goal of the web…”

Have you ever wondered how and why page views became so important to media companies and brands? Quality of reporting and writing quickly took a back seat to the need to make money, thus forcing publishers to churn out as much content as possible. It’s easy to blame content marketers for the rise of spammy content on the web, but the reality is that banner ads on the web were actually invented by journalists and media professionals trying to support their early web-publishing craft. Content marketers just followed their lead.

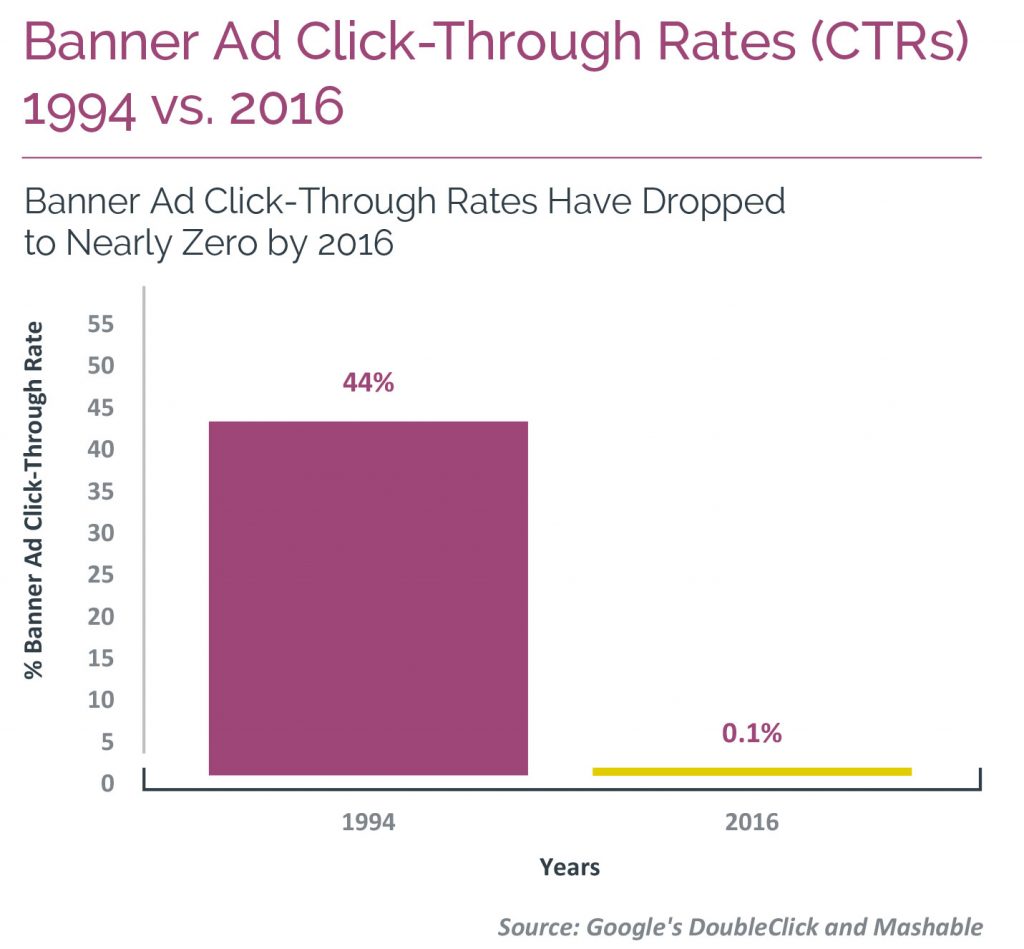

Banner ads proved effective at first: click-through rates (CTRs) began at 44 percent nearly 20 years ago. According to Google’s double-click network, today’s average ad CTR is 0.1 percent, and comScore reports that the average person sees more than 1,700 banner ads in a given month. Meaning the average person clicks on 1.7 banners per month, sometimes accidentally.

Consumers have been vocal about their disdain for display advertising: constant ads pelting the screens of readers and viewers across the web. In response to the growing number of pop-ups and sponsorships on the side rails of websites, ad-blocking technology has exploded over the past few years.

According to PageFair, there are now 198 million active ad-block users around the world, growing 41 percent year-over-year in 2015. This new trend of hiding sponsored pop-ups cost publishers nearly $22 billion last year. Similar to people moving away from pay TV in favor of ad-free networks like Netflix, readers are demanding the same quality experience across the web.

This movement has forced publishers to re-think how to build trust with readers—enough to maintain a sustainable revenue model.

In a recent study, The Importance of Trust for Personalized Online Advertising, Marketing Professors Alexander Bleier, of Boston College’s Carroll School of Management, and Maik Eisenbeiss, of the University of Bremen, studied how trust in a particular business or brand influences the degree to which a person is likely to click on or reject a banner ad.

The researchers found that more trusted retailers saw the CTRs of their ads increase by 27 percent. However, companies don’t establish trust through continuous display advertising; they establish it through continuous storytelling. Today, both media companies and brands recognize that quality brand storytelling is the only sustainable way to build trust with an audience. Both are doing more to build influence, rather than rely on advertising revenue to prop up their efforts.

In the past six years, content marketing has become the center of conversation across marketing departments. CMOs are demanding content, customers are open to brand storytelling, writers are buying homes in the Hamptons and wearing Cartier Love bracelets like the Jenner’s (OK, maybe not), and now there’s more trustworthy content out there than ever before.

The marketing world needed disruption from interrupt advertising. The people wanted sanctuary from commercials and banner ads. But even with all the promise content offered early on, the practice has become exploited, bastardized, and ruined.

What happens when the solution to interrupt advertising becomes equally interruptive?

Like Robert Griffin Jr. III, content marketing was pegged early on as a prodigy sent to solve all of our prayers. Preliminary reports suggested that all brands and media companies had to do was produce content that readers would enjoy.

For enterprise marketing teams, this meant reorganizing their departments to focus on building a digital publication and producing high-quality, original content. Marketers could look to media companies for guidance.

For publishers, this meant working with brands to re-think advertising altogether. Native advertising became a creative solution in which brands paid publishers to create and host relevant information on behalf of the advertiser. This ubiquitous content format now helps media companies sustain their publishing models in the ways display advertising has failed.

Unfortunately, as more brands and media companies invested in various types of content marketing, the greater the competition got, the more confused the marketplace became, and the less effective the tactic overall. For consumers, content marketing became just another distraction, as it flooded their inboxes and social feeds at unprecedented rates.

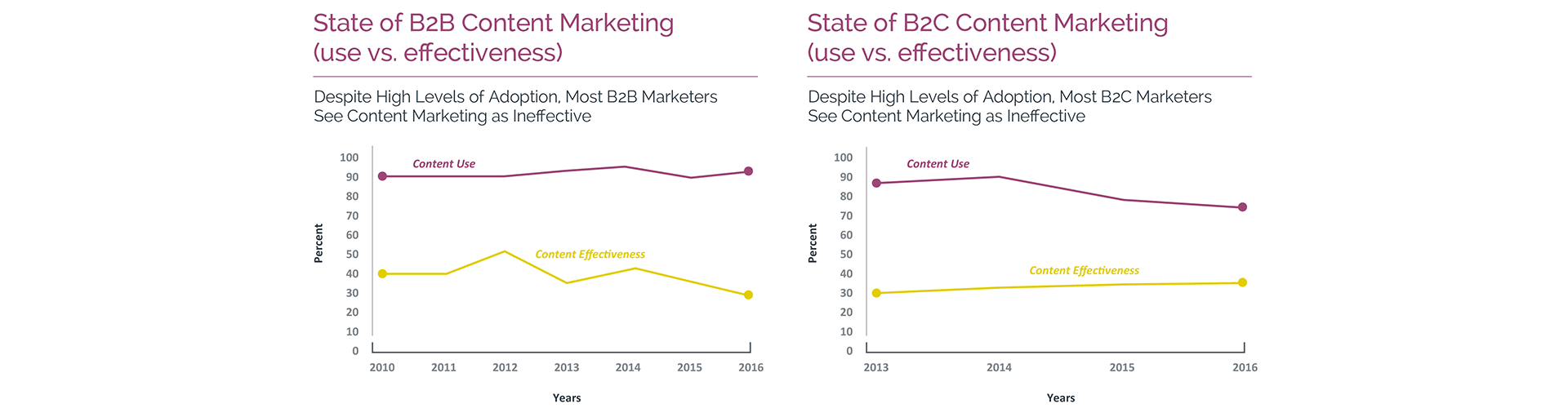

The Content Marketing Institute has mapped the adoption and effectiveness of content marketing across B2B and B2C businesses since 2010. In its first report, 90 percent of B2B and B2Cs indicated that they used content marketing to reach audiences with varying levels of effectiveness (40 percent for B2Bs, 51 percent for B2Cs).

As the years progressed, use of content strategy and its effectiveness have wavered. In the 2016 reports, 88 percent of B2Bs and 76 percent of B2Cs reported investing in content creation. Of those who have invested in the practice, 30 percent of B2Bs and 38 percent of B2Cs say they’re effective.

It’s hard to develop, launch, and maintain an independent digital publication. Brands see the value of content marketing, but when it comes to execution, they don’t know where to start, or they run into corporate red tape.

In many cases, marketers fail to start with the obvious: their purpose. The old publishing mentality of producing more content to increase pageviews still exists, and it perpetuates through marketing copy all over the web. Even though content marketing might be a solution to display and TV advertising, there are those people in the marketing field who aren’t changing the way they work to solve the deeper problem at hand. Whether a brand is trying to engage its audience through TV commercials or sustainable brand storytelling, the experience matters most.

Instead, they’re bringing over the same processes, theories, and measurement standards from legacy channels. It’s no wonder that producing content for content’s sake has invaded every corner of the Internet. And it’s no surprise that media companies are blaming brands—they’re losing audience to these publications at a record pace.

It’s a land grab in which both brand marketers and media executives are trying to be everything to everyone. The pressure to solve this broken system has introduced industry jargon and turns of phrase to exemplify credibility. Self-promoted “influencers” crawl the web touting their experience, but lack the necessary know-how to implement a truly transformative content strategy within an enterprise. Fearful CMOs don’t give middle managers enough runway to test a strategy to its fullest, and untrained strategists spend too much time in the weeds of SEO and social media without understanding the bigger picture.

On top of all of that, marketers are people, too, and they’re dealing with offline pressures of life: raising families, taking care of their health, paying off mortgages, and figuring out whom to vote for president. We’re feeling it at both ends: As a consumer, we don’t want to be “always on,” and as a marketer, we’re paid to find ways to connect with people who just want to be left alone.

It makes you wonder: Is it worth it?

With all of the changes taking place in the marketing industry, technology has taken center stage: more automation, less room for human error. Senior-level decision makers have begun to run their marketing departments like assembly lines, focusing on repetition and specificity over experimentation and agile processes.

A study out of The Ohio State University’s Fisher College of Business found that enterprise organizations replicate success in two core ways: “learning by doing” and “astute self-selection.”

The misconception is that highly innovative brands learn from their successes and their mistakes, and adjust strategies from there. But that assumes most brands allow percentages of unmitigated risk in marketing—and that’s simply not true.

Instead, the study found that successful companies often engage in “astute self-selection.” Meaning, they find something they do well, and they automate and repeat it. The authors write, “In some cases, companies don’t learn so much from what they’ve done in the past as carefully chosen to only repeat those activities with which they have been the most successful in the past and expect to be the most successful in the future.”

The researchers are careful to say that both styles work and have their time and place. But what if “astute self-selection” becomes the status quo in marketing? By only repeating what has worked in the past, marketers are unable to test and experiment with new channels and technologies.

Marketers have found themselves in factory-like roles churning out new versions of the same ideas, and buyers aren’t lining up. It’s like some dystopian world where we’ve divided ourselves and lost sight of what great storytelling is all about: inspiration and entertainment; love and motivation; purpose and self-discovery. That was television’s early promise, what the web sought to reimagine, and what we lost along the way. So how do we get it back?

Breaking out of this mentality requires a shift in infrastructure and mindset.

One central theme mentioned by enterprise marketers today is that they know they need to develop storytelling strategies, but they aren’t sure where to start. In some cases, brands have jumped head-first into content marketing, but haven’t outlined their priorities or purpose as publishers.

This has created an environment in marketing where brands are reorganizing their departments to work more like publishers—before they’ve conducted the necessary research and development work to understand why or how this work will be sustainable.

In recent Skyword research, the company found that of the 38 percent of companies that had reorganized their teams, more than a quarter (26 percent) reported being extremely successful at marketing, compared to just 9 percent of those that hadn’t reorganized.

Many of these enterprise teams reorganized as a way to break down barriers within their marketing departments. Iron Mountain and Tom’s of Maine reorganized their marketing departments to put content at the center of everything they do. But that decision wasn’t an easy one to make, and it was only made after a period of trail, error, and failure.

The Content Marketing Continuum is a brand storytelling spectrum that Skyword uses to analyze the sophistication of a brand’s content marketing strategy. Businesses only producing content to support products and services fall in the “Novice” category, while brands that have embedded story into their culture, like LEGO and Marriott International, fall in the “Visionary” category.

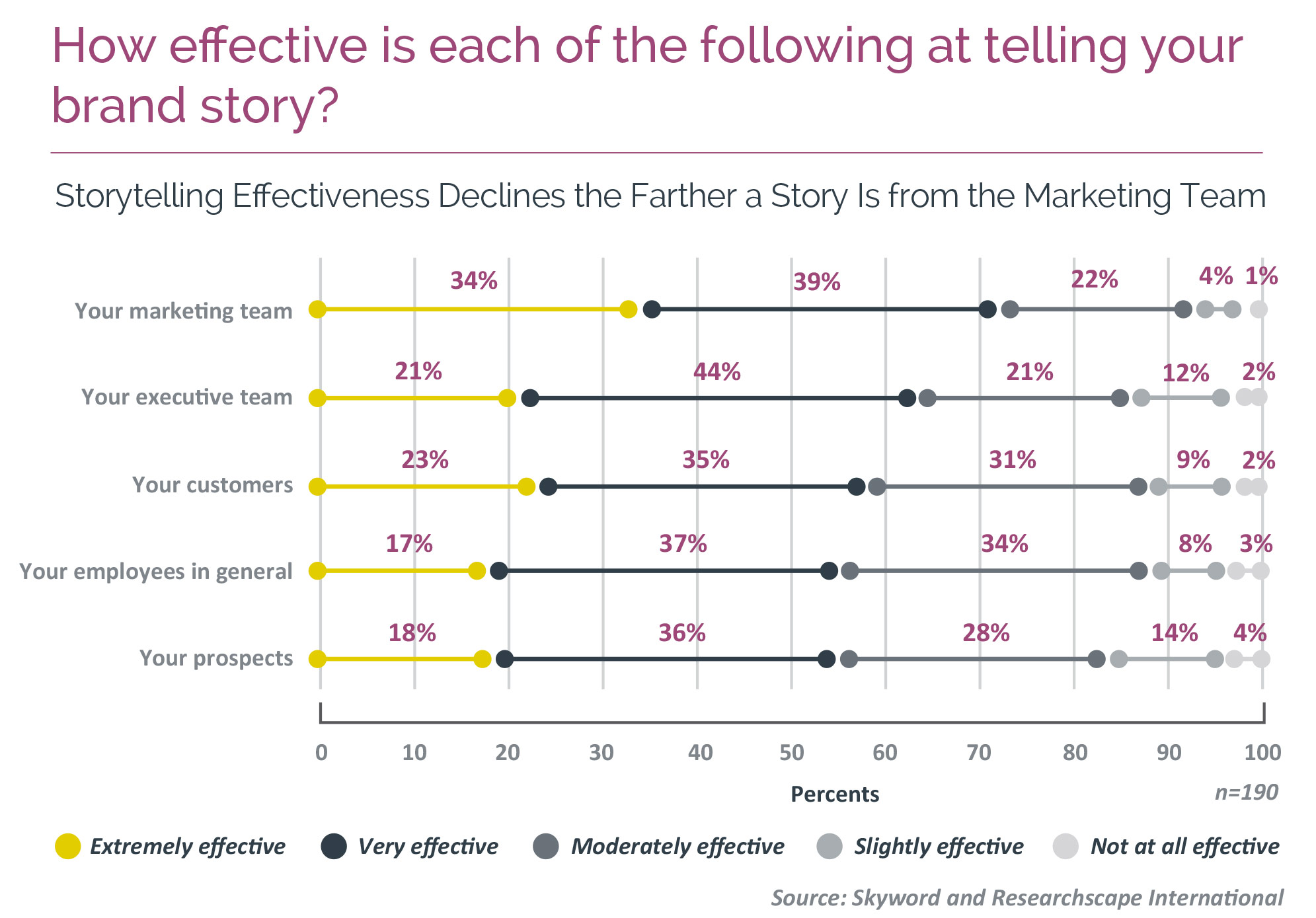

In new research from Skyword, researchers found that storytelling effectiveness declines the more removed the storyteller is from the marketing team. It’s like a game of telephone, where the purpose might be crystal clear when it’s marked up on a whiteboard in an all-marketing meeting, but the more it’s iterated and revised by executives, customers, employees, and prospects, the qualities that made it unique have disappeared.

Seventy-three percent of marketing teams consider themselves to be very effective or extremely effective storytellers. The executive team (65 percent), customers (58 percent), general employees (54 percent), and prospects (54 percent) all lag behind.

A skeptic might look at this data and land on the idea that a higher-than-50-percent benchmark in all areas equates to success. Here’s why they’d be wrong:

We’re at a point in content marketing where there are a few game-changers (i.e. Marriott International, The LEGO Group, General Electric), but the majority of branded publishers fall somewhere in between “I write blogs” and “I’m a managing editor.”

Yet the success produced by these game-changers wasn’t a quick or easy process. In speaking with Michael Moynihan, The LEGO Group’s Vice President of Marketing, for the Content Standard, we got a glimpse into how the company refocused its priorities in 2002 after plateauing in the marketplace.

“We thought the way to grow our business was to find ways for the LEGO brand to be everything to everyone, and we took our eye off the ball of being the best construction toy for children who like to build.”

It’s easy to get caught up in the potential that your brand has to be bigger, better, and more profitable. We found that the best way to grow was to do what we do best, not expand into areas consumers couldn’t readily follow or relate to their understanding of the brand.

Moynihan continues:

“It’s amazing how very simple and aligned words can drive organizational energy and motivate teams to start pulling in the same direction. In crystalizing our Brand Mission and Purpose…and defining the core values with which we seek to achieve [our goals], the Brand Framework has become the roadmap—rally cry—for 15,000 LEGO employees around the world to understand how their work fulfills our greater purpose.”

Marriott International is another example of a brand that had to first understand its purpose as a publisher before stakeholders from around the enterprise would dedicate resources to regular storytelling. But once on board, executives shifted everyone’s mindset away from “this will be valuable because it will book a room” to “this will be valuable because it will make our audience happy.” It had to be an enterprise-wide evolution in order for it to be successful.

“Content marketing can’t be something that Bob down the hall is working on. It can’t be, ‘Go see Bob about some content marketing or whatever.’” – David Beebe, Marriott International’s Vice President of Global Creative and Content Marketing.

Let’s look at the two companies our main characters represent.

Content marketing can’t be something that Bob down the hall is working on. It can’t be, ‘Go see Bob about some content marketing or whatever.“

Iron Mountain abandoned the pressures of always selling and embraced the joys of teaching. By reorganizing departments and rallying teams around storytelling, the company was able to shift away from the mindset that “this content will help generate leads” to one of “now that we’re able to focus on stories, we can measure success by how much we inspire our customers’ work.”

Tom’s of Maine removed the pressures of always pitching product across channels like social media and found relief in aligning the whole company around the idea of empowering its target consumer to lead a more natural life, while caring for both people and the planet. By putting story at the center of everything they do, the company was able to shift away from the mindset of “let’s use social media to support our products” to one of “let’s use every available channel to tell stories that reflect the personality of our brand—from the way we redesign our office to how we greet our customers in 140-characters or less.”

Like Moynihan says, small adjustments to language can uncover a company’s purpose and reveal a marketing team’s “Ah-Ha” moment.

Consumers have changed. They’re empowered by new technology to discover the information they need to make informed decisions about the products they buy, but they’re also pickier about the businesses they buy from.

In the 1950s, product diversification introduced a wide variety of new offerings to people across the country. Over sixty years later, we’re at a period in human evolution where we’re less attracted to the shiny new object and more interested in items and services that mean something real—that enrich our lives like stories.

We’ll never be able to escape the pressures of life completely—there will always be jarring news reports and work emails to respond to. But when we do have time to escape into our dreams and explore our passions, we want to be able to revel in those moments; allow our minds to wander; form memories and be inspired to act. When brands create those moments for us, we don’t care who told us the story; we care how that story made us feel.

As content marketers, we’re all on the continuum, working toward a state where our ideas and the stories we tell permeate across the enterprise and linger in the hearts of our audience. It’s a slow process, and it takes tough decisions to make any progress. We’ve heard how Iron Mountain and Tom’s of Maine are evolving to replace moments of pressure with joy for their customers—now we all just need a framework for moving further along on the content marketing continuum.

As you reflect on the current state of your marketing strategy, focus on finding your purpose as storytellers. Without a clear mission and vision on how to enrich your audience’s lives, you’re doing nothing more than interrupting your audience, whether through commercials, banner ads, or content marketing.

Comments are closed.